Lymphoma can affect bone in a primary or secondary fashion. Primary bone lymphoma is a rare tumor, comprising less than 5% of all bone tumors and less than 1% of all cases os lymphoma.

Primary Bone Lymphoma

Primary bone lymphoma is defined as lymphoma within a single bone with or without regional nodal metastases and the absence of distal lesions within 6 months following the diagnosis. Primary bone lymphoma involving more than one bone without distal metastases is a subgroup of primary bone lymphoma and is called

primary multifocal osseous lymphoma or multifocal primary lymphoma of bone.

Hodgkin lymphoma, usually diffuse histiocytic lymphoma, makes up the majority of cases of primary bone lymphoma. Primary bone lymphoma has the best prognosis of all primary bone malignant lesions.

Primary bone lymphoma tends to affect the pelvis and appendicular skeleton, while primary multifocal osseous lymphoma tends to involve vertebrae more often than primary bone lymphoma.

Secondary Bone Lymphoma

Secondary bone lymphoma is more common and can be seen with both Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Bone involvement can be seen in about 5% of lymphoma cases during the entire course of the disease and is higher in children (25%). The most frequent sites of secondary (metastatic) involvement are the spine, pelvis, and skull.

In Hodgkin lymphoma, secondary involvement may be via hematogenous dissemination or contiguous spread from adjacent lymph nodes, with the sternum being a common site of involvement from adjacent internal mammary lymph nodes. The lesions can be either sclerotic, lytic, or mixed, with sclerotic lesions accounting for almost half of all bone lesions in Hodgkin lymphoma.

Imaging Findings

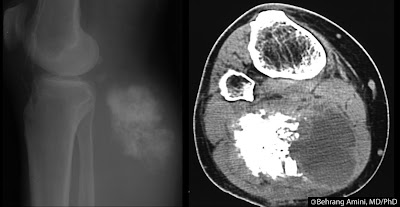

Imaging findings are nonspecific and similar for primary and secondary forms. Radiographic findings are especially nonspecific and can range from normal, predominantly lytic (most common), sclerotic, to mixed. Cortical destruction, extraosseous soft-tissue masses, and periosteal reaction (usually aggressive) can also be seen and indicate advanced local disease.

Radiography tends to underestimate the true extent of the lesion, making MRI and nuclear medicine necessary for proper evaluation. The radiograph above shows a vague lucency involving the proximal humerus, which underestimates the extent of disease seen on MRI and PET.

A sclerotic pattern is seen more frequently with Hodgkin lymphoma, with the ivory vertebrae being a classic presentation. In non-Hodgkin lymphoma, lytic lesions with a permeative pattern are the most common radiologic presentation. In addition, sclerosis can develop following chemotherapy or radiation.

Bone scans are much more sensitive than radiography in detecting osseous involvement, revealing areas of increased radiotracer uptake. PET and MRI, however, are more effective in detecting marrow involvement and lesions without bone remodeling.

CT may reveal cortical and trabecular disruption, periosteal reaction, sequestra, and extraosseous extension. In the case of sclerotic lesions, the relative lack of cortical destruction on CT favors lymphoma over osteosarcoma and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Extraosseous tumor growth with relative preservation of the cortex is another feature of lymphoma best evaluated on CT and MRI, but can also be seen with Ewing sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor.

Another feature of lymphoma best seen on CT is a

sequestrum. Although most often associated with osteomyelitis, sequestra can also be seen in non-matrix forming bone tumors such as lymphoma, fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis.

Marrow involvement is best seen on MRI as T1 hypointensity, but is not specific for lymphoma. T1-weighted images are best for evaluating the extent of disease. T2-weighted and STIR images may reveal low (uncommon), intermediate, or high signal intensity. While sensitive in detecting marrow involvement, T2-weighted and STIR images may overestimate osseous lesions due to the difficulty in differentiating peri-lesional edema from tumor. There may be areas of entrapped marrow fat within the lesions.

Extraosseous soft tissue masses are T1-hypointense and T2-hyperintense and demonstrate diffuse and homogenous enhancement.

Extraosseous tumor growth with relative preservation of the cortex is another feature of lymphoma best seen on CT and MRI, but can also be seen with Ewing sarcoma and primitive neuroectodermal tumor.

Treatment response is best evaluated by histologic analysis, as MRI is not as effective in distinguishing viable tumor from post-treatment changes.

Should be considered in the

differential diagnosis of fat-containing bone lesions.

References

- Hwang S. Imaging of lymphoma of the musculoskeletal system. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2010 Feb;18(1):75-93.

- Hwang S. Imaging of lymphoma of the musculoskeletal system. Radiol Clin North Am. 2008 Mar;46(2):379-96, x.

- Malloy PC, Fishman EK, Magid D. Lymphoma of bone, muscle, and skin: CT findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992 Oct;159(4):805-9.

Between 2% and 25% of patients who undergo vertebroplasty develop cement (polymethylmethacrylate) pulmonary emboli. These are usually asymptomatic and go undetected by operator at the time of imaging. Cement leakage into the paravertebral veins and/or inferior vena cava may be associated with development of pulmonary cement embolism. There may also a correlation between the total number of treated levels and the number of emboli.

Between 2% and 25% of patients who undergo vertebroplasty develop cement (polymethylmethacrylate) pulmonary emboli. These are usually asymptomatic and go undetected by operator at the time of imaging. Cement leakage into the paravertebral veins and/or inferior vena cava may be associated with development of pulmonary cement embolism. There may also a correlation between the total number of treated levels and the number of emboli.